|

This remarkable flag is

one of the earliest, if not the earliest,

surviving examples of the American Flag. Research on

this flag led to some fascinating insights into the

early history of the American Flag that is often

completely overlooked, or only minimally discussed, in

most books and accounts written about the topic. The period

between the first Flag Act of 1777, which established

the thirteen stars and thirteen stripes pattern for the

American Flag, and the second Flag Act of 1794, which

adjusted the flag to fifteen stars and fifteen stripes

following the introduction of Vermont and Kentucky into

the Union, was in fact a period of radical and rapid

change in the governance of the United States of America.

Following the signing of the Declaration of Independence

in July, 1776, the Second Continental Congress set about drafting the "Articles of

Confederation and Perpetual Union" as the governing

document over the national federation of the thirteen

states. On June 14, 1777, while the Articles of Confederation were

still being

drafted, Congress passed the Flag Act of 1777

establishing the thirteen stars and stripes as the flag

of the United States, This first Flag Act was passed

by a wartime Congress presiding over a loosely banded union of

colonial states which had not yet organized under a

federal government charter. It was not until

November 15, 1777, months after the Flag Act of 1777 was already

passed, that Congress approved

the Articles of Confederation, which were not ratified

and in effect until March 1, 1781. While the thirteen original

colonies were united as states in the common cause of

the Revolution and securing their declared

independence from Great Britain, at this early time they still operated

very much as independent states without a democratically

elected national

leader or a strong centralized federal

government.

The Articles of Confederation and Emergence of the

United States Constitution, 1781-1787

Securing victory in the Revolutionary War, which

formally ended with the Treaty of Paris

on September 3, 1783, led to the obvious next step for

the colonies, which was to determine what form the

government of the United States of America would take now that they were

recognized formally as separate and independent of Great Britain. Yet almost

from the beginning, it became clear that the Articles of

Confederation were not sufficiently strong enough to

bind the member states together under an effective

central governance structure. During the war, in 1781, debates about

taxation and raising revenues to begin repaying mounting war

debts proved contentious. Since the Articles of

Confederation did not expressly give Congress the right

to raise taxes, unanimous consent of the member states

was required to do so. Rhode Island refused to consent

to giving Congress the power of taxation, highlighting

the limitations of the Articles of

Confederation as a governance structure to maintain

unity and implement policies supported by a majority,

rather than the totality, of its members. Rhode Island,

in particular, proved to be a challenging partner in the

federation, strongly protective of its state's rights.

This was understandable to a degree, since there did not

exist significant guarantees of citizens' rights, such

as those which would come a decade later with the

passage of the Constitution's Bill of Rights. It is

Rhode Island's intransigence with regards to ceding

powers to a federal government that

is likely directly related to the existence of this

twelve star flag.

By

1786, struggling fiscally under the burden of debt

from the Revolution and unable to pass measures under

the Articles of Confederation to jointly remedy the

burden, leaders of several states

proposed to convene to revise the Articles of

Confederation. The "Meeting of Commissioners to Remedy

defects of the Federal Government" in Annapolis drew

few attendees, but it laid the foundation for a second

meeting in Philadelphia the following year. When the

States finally met in Philadelphia to review the

Articles of Confederation in June, 1787, Rhode Island

did not send delegates, and only twelve states were

represented. The reviewing body, which became the

Constitutional Convention, determined that rather than

attempting to remedy the defects of the Articles of

Confederation, a new governing charter, the United

States Constitution, would be drafted. Rhode Island,

still

wary of federal interference in its practices of

printing its own paper money as well as other perceived

threats to its autonomy and its citizens' religious and

personal freedoms, not only abstained from

attending the

Constitutional Convention, but also did not attend the

signing ceremony, making it the only one of the 13

original states not to be a signatory to the

Constitution.1

Ratification of the United States Constitution, 1787

The United States Constitution required nine states to

ratify it before it came into effect. One by one, the states began holding

ratification conventions to discuss and ratify the

Constitution. The country watched as each state debated

the Constitution and voted to ratify it.

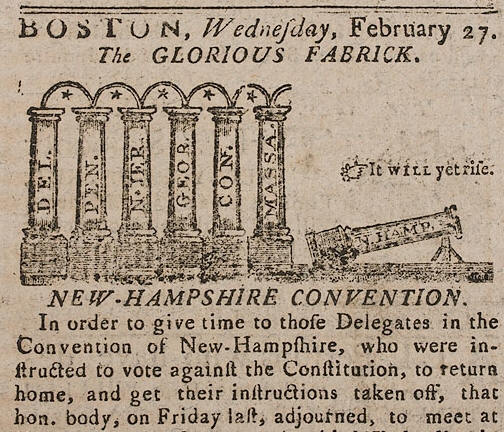

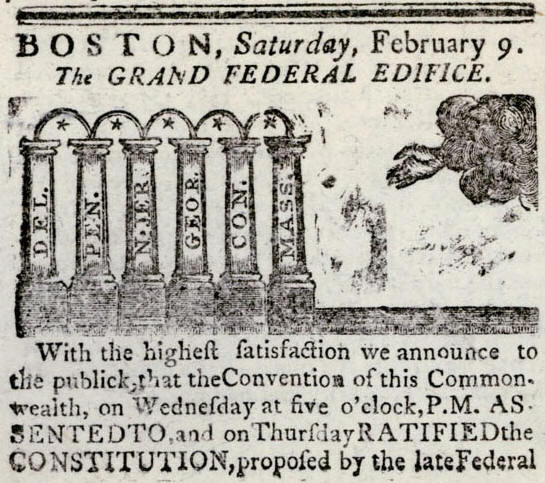

A running

political cartoon in the Massachusetts Centinel

illustrates how the country anticipated each ratifying state

as a new "star" in the new country's constellation.

Flouting the letter and spirit of Article Seven of the

proposed Constitution, the Rhode Island General

Assembly called for a statewide referendum rather than a

state convention, and Rhode Island voters overwhelmingly

rejected the Constitution on March 24, 1788. By the time

of Rhode Island's rejection, six states had already

ratified the Constitution.2

|

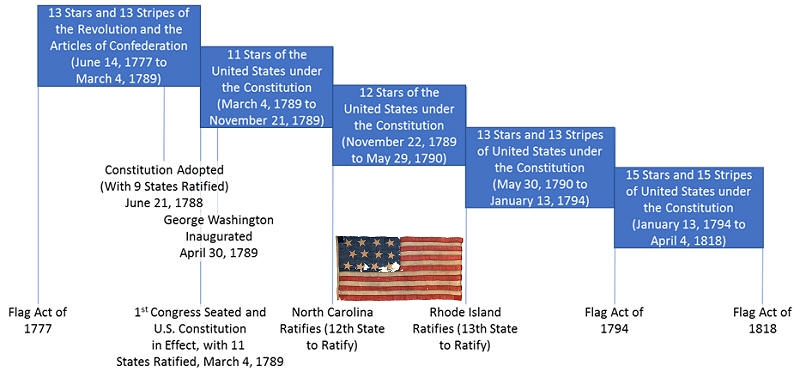

Upon ratification of the Constitution by the

ninth state, the United States of America

entered into an unusual status which, from a

flag history perspective, is often overlooked.

The transition of the governance of the United

States from the Articles of Confederation to the

Constitution was not instantaneous. Once the

Constitution was officially adopted on June 21,

1788, it was agreed that on March 4, 1789,

governance under the Articles of Confederation

would officially end and the Constitution would

come into effect.3

Virginia ratified on June 25,

1788, and New York ratified on July 26, 1788.

But two hold-out states--North Carolina and

Rhode Island--had still not ratified the

Constitution by the time it came into effect. Thus, the

first government of the United

States of America under the Constitution of the

United States began with just eleven states.

On March 4, 1789, the 1st United States Congress

convened in New York City and declared the new

Constitution to be in effect. Only the eleven

states that ratified the Constitution had

Representatives and Senators seated in Congress.

“At sunset on the evening of

March 3d [1789], the old Confederation was fired

out by thirteen guns from the fort opposite

Bowling Green in New York; and on Wednesday, the

4th, the new era was ushered in by the firing of

eleven guns in honor of the eleven States that

had adopted the Constitution.4

The States of Rhode Island and North

Carolina, now severed from the American Union,

were as independent of each other as England and

France. "All sea-captains," said a Providence

newspaper5,

"belonging to this State, will sail under the

sole protection of the State of Rhode Island,

having no claim to the flag of the United

States, for the eleven confederate States are,

in fact, the United States."6,

7

George Washington, elected on February 4, 1789

by a slate of electors from ten states (New York

failed to field a slate of electors, and North

Carolina and Rhode Island had not ratified the

Constitution), was inaugurated on April 30,

1789, as President of just eleven states. A

first-hand description from Washington's journey

from Mount Vernon to New York City for the

inauguration, makes an interesting observation

about the flags flying during his travels:

“The

greatest day that Gray's Ferry bridge ever knew

was April 20, 1789. On that day George

Washington crossed it on his way to New York to

become first President of the nation which his

sword had called into being. The "Columbian

Magazine” for May, the following month,

contained a fine copper-plate engraving from a

drawing by Charles Wilson Peale of this bridge

as decorated for the occasion, and the following

description:

The

whole railing, on each side of the bridge, was

dressed with laurels interwoven with cedar. A

triumphal arch 20 feet high, decorated with

laurel and other evergreens, was erected at each

end in a style of neat simplicity; under the

arch of that at the west end hung a crown of

laurel, connected by a line which extended to a

pine tree on the high and rocky bank of the

river where the other extremity was held by a

handsome boy, beautifully robed in white linen;

a wreath of laurel bound his brows, and a girdle

of the same his waist. Eleven colours were

planted on the north side of the bridge, in

allusion to those states which have ratified the

constitution; on the south side were two others,

one emblematical of a new acra, the other

representing Pennsylvania—it was the flag which

captain Bell carried to the East Indies, being

the first ever hoisted there belonging to this

state. At the east end of the bridge a striped

cap of liberty was elevated on a pole about 25

feet in height, from which spread a

banner-device, a rattle-snake, with the motto,

"Don't Tread On Me." A large signal flag was

hoisted in the ferry gardens, to give notice of

the general's approach to those who were posted

on the other side of the Schuylkill. On the top

of the ferry post on the west side, a banner was

displayed—the device a sun with this motto,

“Behold the Rising Empire.” On the opposite

shore flew a banner, alluding to commerce-motto:

“May Commerce Flourish.” The ferry boat and

barge were anchored in the river, and displayed

a variety of colours, particularly a jack

bearing eleven stars. About noon the illustrious

Washington appeared and as he passed under the

first triumphal arch the acclamations of an

immense crowd of spectators rent the air, and

the laurel crown, at that instant, descended on

his venerable head. His excellency was saluted

on the common by a discharge from the artillery

and escorted into Philadelphia by a large body

of troops, together with his excellency the

president of the state, and a numerous concourse

of respectable citizens.”8

|

"ELEVEN STARS, in quick

succession rise..."

- August 2, 1788, The Massachusetts Centinel

Source:

Teaching American History |

The

American Flag, between Nine and Twelve Stars, June 21,

1788 to May 29, 1790

Several other 19th and

20th century histories the American

Flag and the events surrounding the tumultuous 1787-1790

period where the Constitution was being ratified,

adopted, and placed into effect, make note of the

unusual circumstances of the number of stars on the

flag. Some repeat the observation of the eleven star

jack present in first hand accounts of Washington's

inauguration journey and others elaborate on other

observed reports of the presence of flags with fewer

than thirteen stars.

“It was, of course, under the Stars and

Stripes that the Constitutional Convention met at

Philadelphia, in 1787, and formulated the fundamental

law of this republic; it was under it that the States

one by one ratified the Constitution and held the first

election of a President and Congress; and it was under

the same banner that in 1789 Washington travelled from

Mount Vernon to New York, and was there inaugurated and

installed as the first President of the United States.

It is said that among the decorations in the city of

Philadelphia as he passed through there was displayed

for the first time the ‘American Union Jack,’ consisting

simply of the canton and its stars, without the stripes,

and that it contained only eleven stars;

North Carolina and Rhode Island not yet having ratified

the Constitution. It appears, moreover, that some other

flags were thus and for the same reason made without the

full number of thirteen stars. Thus some are said to

have been displayed with nine stars

immediately after the ratification of the Constitution

by New Hampshire, the ninth State to do so, at which

time, according to its own provision, the Constitution

was established in full force and effect. A little

later, on July 4, 1788 [sic] there was at Philadelphia a

great celebration of the ratification of the

Constitution, and many flags with ten stars were

displayed, Virginia having also by that time

given her adherence to the instrument. Such adding of

star after star to the Flag as the remaining States

ratified the Constitution may be regarded as

foreshadowing the similar adding of stars as new States

in later years were created and admitted to the Union.”

- The

National Flag, A History, by Willis Fletcher Johnson,

The Riverside Press, Cambridge, Houghton Mifflin

Company, 1930, pp. 68-69.

“When Washington passed through

Philadelphia April 20, 1789 en route to New York to

assume the office of President he was received with

distinguished honors In the river were boats gayly

adorned with ensigns among which was what was then a

novelty an American jack which bore eleven stars

representing the eleven States which had at that time

ratified the Constitution.”

- History

of the flag of the United States of America, by George

Henry Preble, Second Revised Edition, Boston, A.

Williams and Company, 1880, pp. 297-298.

“One banner had been made up in June,

1788, after New Hampshire's ratification (the ninth

state) had ensured the adoption of the new Constitution.

It had but nine stars and nine stripes.”

-

Flags of the U.S.A., by

David Eggenberger, Crowell, 1964, p. 103.

“It would be interesting to know how

large a percentage of intelligent American citizens

remember that at Washington’s inauguration as our first

President, flags bearing only eleven stars

were displayed…”

-The North American Review, Vol. 224,

No. 835, published by the University of Northern Iowa,

Jun-Aug 1927, p. 188.

“The original thirteen States were New

Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, New

York, Delaware, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland,

Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia.

Some of the flags used when only twelve of the States

had ratified the articles of the Convention bore

only twelve stars.”

-

Declaration of Rights of

American Colonies, 1765 and 1774, Declaration of

Independence, Articles of Confederation, Constitution of

the United States and Constitution of the State of

California, published by University of California,

Berkeley, Superintendent State Printing, 1909, p.14

Eleven, Twelve and Finally, Thirteen

The United States of

America, under the Constitution of the United States,

thus operated as a country for a period of nearly 9

months (262 days, from March 4, 1789 to November 21,

1789) with a union of eleven states until North Carolina

ratified the Constitution. It operated as a country for a period of more than 6 months (188 days, November

22, 1789 to May 29, 1790), with a union of twelve states

until Rhode Island ratified the Constitution, finally

bringing the Union to thirteen states and thirteen

stars.

The situation of the

country during these times was very publicly debated and

discussed, and it was only after significant pressure

was applied to Rhode Island, in the form of threatening

to regulate trade with it as though it were a foreign

country, that Rhode Island finally consented to holding

a two ratification convention sessions in March, 1790

and May, 1790, resulting in ratification on May 29,

1790. The question then, is, if a flag maker were asked

to make a Stars and Stripes flag between November 22,

1789 and May 29, 1790, how many stars would they likely

put on the flag? Given Rhode Island's very public and

adamant rejection of the Constitution, even declining to

participate in the process of debating,

drafting, or ratifying it, and declining any governance

union with the newly formed United States of America, it

is very plausible that the flag would have twelve

stars to represent the current union at the time. It is

reasonable too that the flag maker would choose, and be

equally correct with, either twelve stripes or thirteen

stripes. Maintaining the thirteen stripes would preserve

the symbolism from the earliest Continental Colors

and Flag Act of 1777 design of our flag, representing the thirteen original

colonies and states of the Revolution. Even before the Second Flag Act

of 1794 came into effect, which fixed the number of stars at fifteen and the

number of stripes as fifteen following Vermont and

Kentucky statehood, the practice of including

the number of stars to represent the actual number of

states in the Union, thus making the design of the flag

inclusive, was debated vigorously. Regardless of the

debate, the prevalent practice was to add stars with the

addition of states. With the Third Flag

Act of 1818 the official number of stripes reverted to the symbolism of the original

thirteen states of the Revolutionary period, but to this

day, the number of stars on the flag represents, as it

always has, the

number of states in the Union.

This

Twelve Star Flag

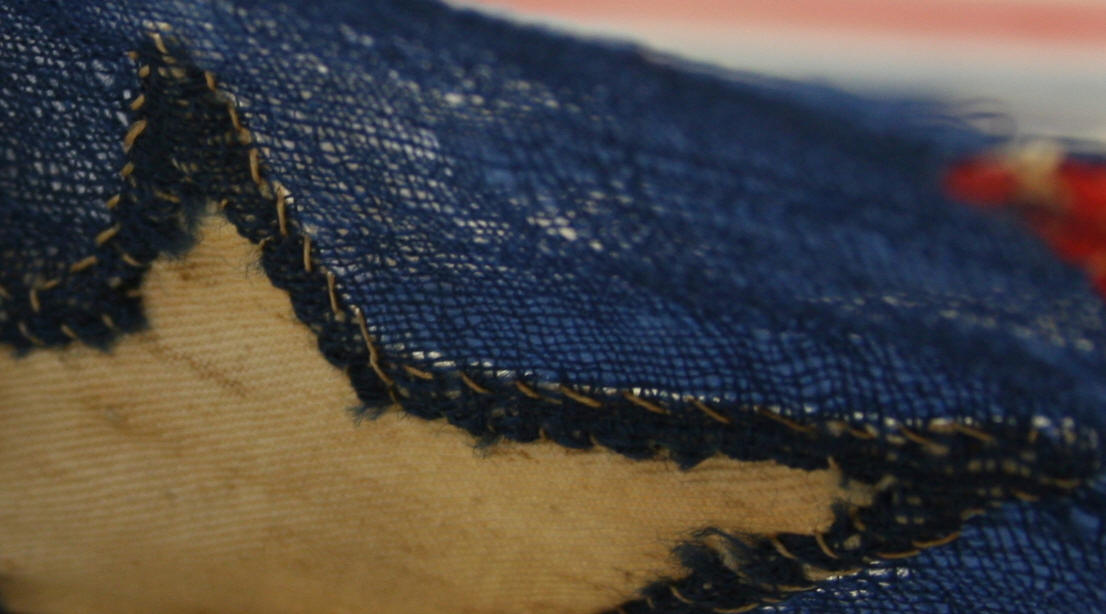

All of the physical

characteristics of the twelve star flag at hand show

it being constructed of fabrics made prior to

the widespread adoption of mechanical looms in England

during the Industrial Revolution at the end of the 18th

century. The wool fabrics of

this flag are made of hand spun yarns and hand loomed

wool bunting. It is a coarse, irregular weave that is only seen on a small

handful of the very earliest flags known which typically

date to the War of 1812 or earlier. In particular, this

flag shares many traits of construction and materials

with a rare 13 Star American Flag that dates to the

1790s and flew over the Old Sandy Point Lighthouse in

New York. That flag surfaced at auction in 2007 and was

examined by flag scholars at the time and confirmed to

be an early Federal Period flag. Its construction and

materials were all consistent with circa 1790s flag

making. The flag is now in the Zaricor Flag Collection,

ZFC2497. Comparisons between IAS-00463 and ZFC2497

show strikingly similar materials and construction

techniques, as seen in the photos below.

|

12 Star, 13

Stripe American Flag

circa 1789-1790 (IAS-00463)

|

13 Star, 13

Stripe American Flag, Old Sandy Point Lighthouse, circa 1789-1795 (ZFC2497)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yet another

interesting aspect of the twelve star flag is

the fact that the maker left

space to the left of the central row of stars

for the addition of another star to bring the

total to thirteen. This would make complete

sense if the flag was made between November,

1789 and May, 1790, with the expectation that

eventually Rhode Island (or another state) would

become the thirteenth state. The pattern is clearly an

approximation, minus the one star, of the

prevalent 4-5-4 pattern of thirteen star flags

which was most seen in depictions of thirteen

star flags from

the early days of the Republic. A modified image

of the flag shown at the right shows the flag

with the full complement of 13 stars. Given the

size of the stars on the flag, and the space

available, the flag maker could have fit another

star but chose not to, making it more likely

that the omission was intentional, rather than

accidental. |

A modified

image of the flag with the 13th star added.

(Note: The top-right star was taken and

mirrored, verifying that the space is sufficient

for stars of the same size as the current ones

on the flag). |

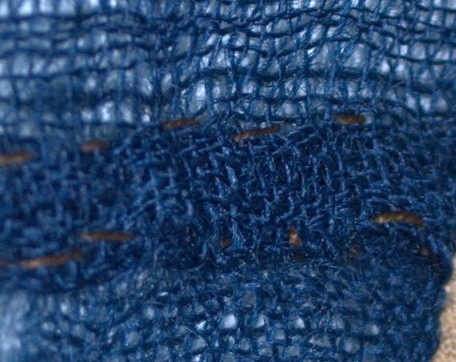

The linen of the

stars is of fine quality for American

manufacture in the 18th century. The linen

threads are home spun and the plain weave of the

linen is approximately fifty threads per inch,

which is the range of the highest quality linens

produced in the colonies and original states in

the 18th century. Coarse linens in the range of

sixteen threads per inch, mid-range linens of

twenty-seven threads per inch, and higher

quality linens of fifty threads per inch were

all grades of linen woven in the American States

in the 18th century. Linen of up to ninety

threads per inch, the finest quality 18th

century linen fabric for sheeting or shirting

materials, was imported from Ireland.9

|

|

Note the irregular sized

hand spun yarns and hand woven linen

fabric of the stars. |

|

The gauge of the linen

star weave is about fifty threads per

inch, the finest quality

woven in 18th Century America.

|

|

The stars are a fine

linen weave, while the hoist is a coarse

linen weave. Note the similar sheen and

coloration of the fabric.

It is possible the linen is from the

same weaver, just two different gauges.

(Photo taken with flash)

|

All indications

from the flag's construction and materials, as

well as its star pattern and number of stars, is

that the flag dates to the very first thirteen

months of the United States of America as a

nation under the Constitution. The flag would

have been correct, for the number of stars

corresponding to the number of states under the

Federal Government, during the first term of

George Washington's presidency, following the

ratification of the Constitution by North

Carolina but before the ratification of the

Constitution by Rhode Island.

1

Rhode Island State Government Website,

U.S.

Constitution Timeline

2

Wikipedia Timeline of the Drafting and Ratification of

the United States Constitution

3

https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/u-s-constitution-ratified

4

Massachusetts Centinel, March 14; also Maryland Journal

and Baltimore Advertiser, March 13, 1789.

5

The United States Chronicle, March 3, 1789.

6

"At the first convention in North Carolina the

Constitution was not ratified; but at a second

convention held in November, 1789, it was adopted by a

majority more than two to one, the vote being one

hundred and ninety-three in the affirmative and

seventy-five in the negative. [The official journal

gives the vote 194 to 77.] The Legislature of Rhode

Island, during the session in September, had sent an

address to 'The President, the Senate, and the House of

Representatives of the Eleven United States of America

in Congress assembled,' in which were contained

explanations of the course pursued by the State in not

adopting the Constitution." – (Sparks's Washington, vol.

x., p. 67.)

7

History of the Centennial celebration of the

inauguration of George Washington as first President of

the United States, by Clarence Brown Winthrop, published

by D. Appleton, New York, 1892, p. 4.

8

The Historic Bridges of Philadelphia, An Address

Delivered Before the City History Society of

Philadelphia on Wednesday, October 12th, 1910, Frederick

Perry Powers, published by The Society, January 1914,

pp. 285-286.

9

The Material World of Cloth: Production and Use in

Eighteenth-Century Rural Pennsylvania, by Adrienne D.

Hood, The William and Mary Quarterly, Material Culture

in Early America, Vol. 53, No. 1, Jan., 1996, published

by the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and

Culture, p. 56.

|